Louise Brooks was an American actress who, while

relatively unknown during the height of her career, has become synonymous with

the glamour, decadence, and social change of the 1920’s. While the majority of

her career was spent in Hollywood and on Broadway, today she is best remembered

for three films that she made in Europe; German expressionist films Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl and French production Prix de Beaute (a/k/a Miss Europe). This week the spotlight will be

turned on one of the most unusual and daring of Brooks’ films, G.W. Pabst’s

Weimar morality tale Diary of a Lost Girl.

Acting in many ways an answer to Pandora’s

Box’s noir-esque celebration of Berlin’s

underworld at its most debauched, the film casts a critical eye upon the

hypocrisy of German high society while exploring the desperation and

hopelessness that was driving Weimar-era Germany onto the path of

self-destruction.

|

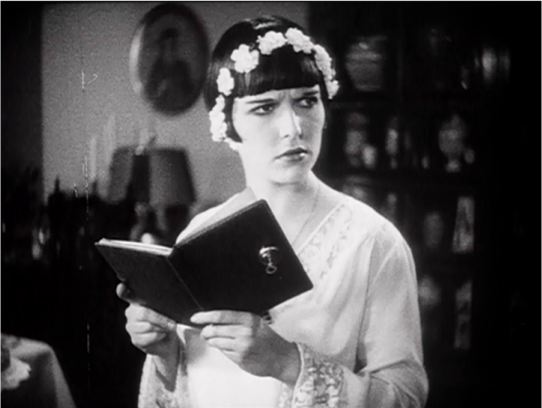

| Who are you callin' lost?! |

The story begins with idealistic schoolgirl Thymian

Henning (Louise Brooks) celebrating her confirmation, only for the festivities to

be dampened by the dismissal of her beloved governess. Thymian’s girlhood

ideals are soon shattered when she learns that her governess, Elisabeth

(Sybille Schmitz), had been dismissed after she had become pregnant as a result

of her affair with Thymian’s pharmacist father (Josef Rovensky). When it is

revealed that Elisabeth drowned herself after losing her job, Thymian turns to

her father’s drug store assistant (Fritz Rasp), who betrays her trust by using

one of the drugs in her father’s store to drug and date-rape her. When her assault

results in the birth of her illegitimate daughter she is presented with an

ultimatum by her family; marry her rapist and legitimize her child or enter reform

school. When she refuses to follow her parents’ plan she is disowned by her

family (who seize custody of her daughter) and then forced into a brutal home

for wayward girls. After reaching her breaking point she teams up with one of

the girls at the home (Edith Meinhard) to plan an escape, which leads them into

the sordid world of prostitution. In a stark break with social norms of the

era, the film then reveals how entering the sex trade ultimately puts Thymian

on the path to her salvation as she reclaims her sexuality, becomes a shrewd businesswoman,

and even finds love with a fellow outcast (Andre Roanne).

|

| A toast to Louise Brooks! |

While the plot follows the melodramatic conventions common

in silent film, Diary of a Lost Girl also

contains valid social criticism of its era. In its portrayal of the double life

of Thymian’s publicly moral but privately corrupt father, the film highlights

the hypocrisy of society in Weimar Germany. Similarly, the film is careful to

show that while Thymian routinely faces cruelty at the hands of supposedly

respectable citizens such as her father and his assistant, she finds acceptance

amongst her fellow outcasts in the city’s underworld. The film also calls women’s

limited rights and restricted roles in society into question through its

portrayal of its heroine’s journey. By portraying its heroine as a ‘fallen

women’, albeit through no fault of her own, the film calls the sexual double

standards of its era into question and calls for tolerance. The script further

reinforces its call for women’s rights by showing that it is only when Thymian reclaims

control over her finances and sexuality that she is able to move forward and

lead a productive life of her own choosing. While the film does veer toward

sentimental moralizing in its final act, its damning critique of Weimar society

was nothing short of astounding for its time and foreshadowed the ways in which

the Weimar Republic’s failure would ultimately lead to the rise of the Third

Reich.

The film’s cast provide an adequate portrayal of the

script, but much of the acting is limited by the excesses common in silent

cinema. Josef Rovensky aptly captures the outward rigidity and private

decadence of Thymian’s father. Fritz Rasp is appropriately sleazy in his

portrayal of Thymian’s father’s predatory assistant, Meinert. Edith Menhard

infuses her role as reform school student, Erika, with an endearing feistiness.

Even while surrounded by apt performances, the film truly belongs to Louise

Brooks, who portrays Thymian’s heartbreaking vulnerability as a betrayed young

girl and guarded hardness as a world-weary woman with equal skill.

Far more than just a piece in the cinematic legend of

Louise Brooks, Diary of a Lost Girl

is an apt social critique of both the social excesses and constrictive social

norms of the 1920’s. The film defied the censors of its era by not only

sympathetically portraying an ordinary girl’s fall from grace, but also showing

the ways in which, with a little tolerance and kindness, she and others just like

her can still triumph. For a look into the dark side of the 1920’s, take a peek

at Diary of a Lost Girl.

No comments:

Post a Comment