It is often said that the best way for an artist to

create meaningful work is for them to portray that which they know best. As a

result, it is little wonder why one of the most enduring portrayals in art is

the struggle and sacrifice of the artistic lifestyle. From consumptive

bohemians, to mad painters, to reclusive writers, many of the most raw

characterizations in modern storytelling are those of artists striving to

achieve success and fulfillment regardless of the cost it may require. While

each art form entails its own set of challenges, one of the most demanding of

art forms is dance, particularly ballet. Unlike ancient eastern dance

traditions designed to work with and accentuate the body’s natural movements, ballet

captures audience’s attention by revealing the beauty of the human form beyond

the limits of everyday movement. Similarly, while modern dances thrive upon

spontaneity and improvisation, ballet is a rigorous art form, which requires

the utmost precision in each of its choreographed movements. By its very nature

ballet is an art form which is consuming, elite, and inaccessible; in short it

is the ideal vehicle through which to explore the passion, doubts, obstacles,

and triumphs of life as an artist. As a result, there have been numerous books

and films which have used ballet to portray diverse characters facing obstacles

ranging from aging (The Turning Point),

to unemployment (Waterloo Bridge), to

political oppression (White Nights),

to personal loss (Save the Last Dance).

Despite the many critically and commercially successful ballet films, the film

that many critics and viewers continue to immediately think of when they heard

the word ‘ballet’ is the 1948 British drama The

Red Shoes.

| Ballet; the stuff nervous breakdowns are made of |

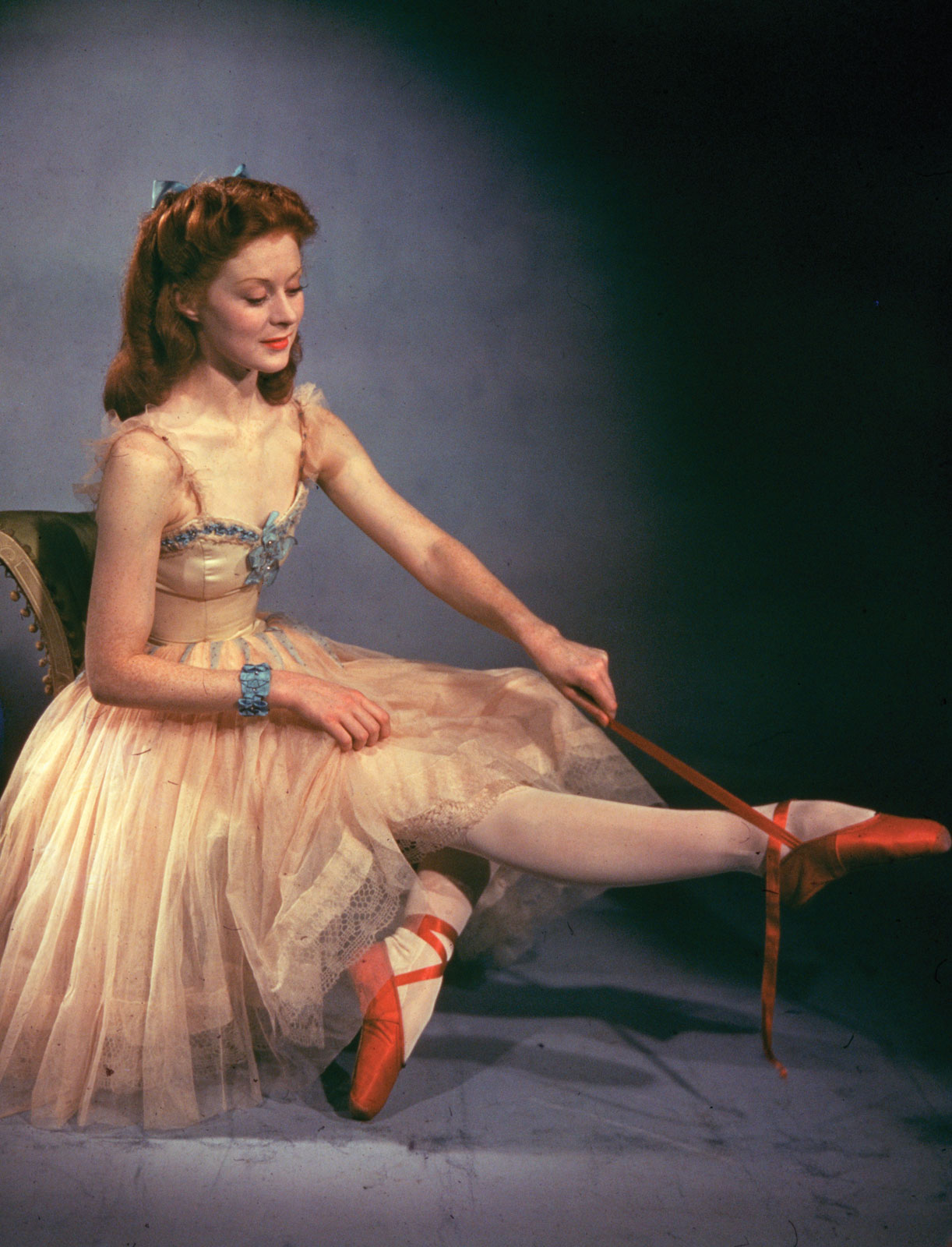

The story of The

Red Shoes is a deceptively simple one; inexperienced but passionate dancer,

Vickie (professional ballerina Moira Shearer), joins an elite ballet company

where she achieves the success she’s always dreamed of, only to become

conflicted between her professional goals and personal needs. While the

conflict between love and art was already a well-worn theme even in 1948, what

the film lacked in original storytelling it made up for in accuracy, visual

innovation, and emotional honesty. Few dance films can compare to The Red Shoes in terms of attention to

detail and realism. Rather than focusing upon the glamour of the performances,

the film spends most of its time backstage, as it shows the painstaking work

that goes into a ballet from its first draft to its final rehearsal. In this

way the film provides an insider’s perspective to viewers who are unfamiliar

with the world of professional dance and pays apt tribute to the men and women

who tirelessly work to bring that magical world to life. The film even goes so

far as to populate its cast with professional dancers rather than utilizing

established actors and body doubles. The film also accurately portrays its

heroine’s struggle for success rather than relying upon the cliché of a

meteoric rise to stardom, as Vickie frustratedly works her way through the

ranks of the ballet company over time.

The film approaches its characters with similar

realism in its exploration of daily life in a ballet company populated with a diverse

array of three dimensional characters. Despite the film’s age, The Red Shoes is remarkably

refreshing in the way that it treats its

story as one of a particular dancer working in a specific company rather than

as a commentary upon ballet, dance, or art at large by avoiding typical clichés

such as abusive directors, ego-maniacal stars, and petty rivalries. In this way

the film ensures that the audience is able to invest in the characters as

though they were real people, which in turn lends the relationships and

conflicts between the characters emotional weight.

|

| A girl and her best frenemy; toe shoes |

Today, another ballet film has taken center stage

using a very different approach. In the 2010 psychological thriller Black Swan, Natalie Portman plays

similarly impressionable and eager dancer, Nina, whose quest for stardom takes

a disturbing turn. In order to provide viewers with insight into Nina’s

fractured mind the characters, plot, and visuals take on a sinister quality

befitting a horror movie’s haunted house rather than a typical theater. Because

the story is told from an unstable character’s perspective, the world of ballet

quickly escalates from a competitive, but fulfilling, working environment to an

elaborate prison in which dancers torture their minds and bodies in order

impress fickle audiences and lecherous directors. Although the fantastic

elements heighten the surreal atmosphere and suspense, they also bring the film

dangerously close to caricature as Nina is constantly surrounded by the very

stock characters that The Red Shoes

widely avoided as she is alternately sexually harassed by her volatile

director, threatened by a bitter ballerina forced into early retirement, and

tormented by the impossible expectations of her ex-dancer stage mother. This

tendency toward camp is most obvious in Nina’s one-note abusive relationship

with exploitive director Thomas LeRoy (Vincent Cassel), which sorely lacks the

subtlety and complexity that made Vickie’s relationship with impresario Boris

Lermontov (Anton Walbrook) both fraught and fascinating. Through its unabashed

sense of melodrama, Black Swan

creates its own surreal world of light and shadow in which everyone and

everything poses a potential threat, which works wonderfully for a

psychological thriller, but fails to shed any light or add any dimension to the

public’s understanding of ballet.

| When did things get all Lewis Carroll around here?! |

Nina’s struggle with her unraveling psyche, for all of

its flash and theatrics similarly fails to resonate when compared with the much

more relatable and timeless conflict that proves to be Vickie’s undoing. On the

dvd box and in critics’ summaries, Vickie is described as being torn between

‘love and dance’. Although this statement is accurate given the fact that she

is forced to choose between her position in the company and her marriage to its

temperamental composer, Julian (Marius Goring), there is also another more

resonant struggle that she faces; the conflict between career and family. Today

we often hear about the conflict between career and family and the difficulty

of balancing the two is hotly discussed and debated. At the time of this film’s

release, this debate was more than a mere talking point; it was the frontier

faced by an entire generation of women who had held down the home-front by

managing homes and taking jobs as the men in their lives fought overseas in

WWII, only to be forced back into their former roles when peace returned. In

her attempt to balance her marriage and her career, Vickie simultaneously faces

another, even greater, challenge to find her place in a changing society. It is

through this battle within its heroine that The

Red Shoes rises above its ‘dance movie’ premise and becomes a true tragedy

when Vickie finally makes the ultimate sacrifice in order to escape a world in

which she cannot be her true and complete self.

Despite their drastically different approaches to

their stories, the films share a number of striking similarities beyond their

focus upon ballet. Both films tackle the emotional toll of dedication to art,

with Black Swan taking this idea to a

chilling end. The Red Shoes and Black Swan also share breathtaking

visuals that border on the surreal as the fairy tale landscapes of the

performances not only come to life, but expand to permeate the characters’

entire worlds. It is these visuals that not only transport viewers into the

world of both heroines, but also provides audiences with crucial insight into

how each woman perceives that world. The most notable similarity, however, by

far is the ambiguous endings to both films that leave viewers spellbound as they

continue to ponder if it the fates of Vicky and Nina were accidents, deliberate

or just two more casualties of the dark side of dance. Both films succeed at telling very different tales set within the ballet world, but once the initial lights came on following Black Swan the shock of the film's darkness faded while I was still haunted by Vickie Page and the tragic end she was driven to by The Red Shoes.

| What a little hard work and psychosis can accomplish... |

No comments:

Post a Comment